ABOUT THE PROJECT

OUR GOAL

‘KEEPING EMPLOYEES ON BOARD’ aims at producing tools and methodologies to facilitate the transition from the work environment into a learning environment, this way upskilling pathways for 55+ employees into workplaces requiring 21st century skills.

SPECIFIC OBJECTIVES

Addressing digital literacy (computational thinking skills, basic ICT skills, media literacy, information skills); workplace culture

(communication, collaboration, self-regulation, social and cultural skills) and innovation and adaptation (problem solving, creativity, critical thinking). In doing so we aim at :

- instigating a dynamic in the workplace: a shift of view that puts the workplace forward as the micro-society that it is

- making learning opportunities more accessible for employees aged 55 and above

- giving employers and employees tools and methods to ‘keep employees aged 55 and above on board’, meaning: keeping the same job with the same employer; or job-creating a new job with the same employer; or making a meaningful transition into a new employer

TARGET GROUP

- employees aged

- 55 and up (primary target group) employees under the age of 55

- employers

FROM A WORK ENVIRONMANT INTO A LEARNING ENVIRONMENT?

- By sensitizing on the fact that 21st century skills are already present among employees.

- By establishing the ground for the empowering dynamic of employees both being teachers and learners.

- By breaking down the 21st century skills into 3 manageable clusters of skillsets.

- By supporting doable and durable implementation of lessons learned.

- By disseminating lessons learned in the field through digitization into freely accessbile webinars.

- The quality of the train-the-trainer modules assessment is based on the EQAVET principles. These principles also guide us towards standardisation and maximalization of dissemination of learning outputs.

- By embedding dissemination in the process : offline as well as online output is made available in 4 languages and is actively promoted through newsletters; stakeholder meetings; the conference and an online inspiration toolbox.

EXPECTED OUTPUTS

- online the train-the-trainer courses; guidelines; accessibility on an online platform

- online learning material for 5 intensive courses

- vital craftmanship and mental retirement (protocol for the creation of support for learning opportunities)

- digital inclusion as a gateway to enhance 21st century skills

- course design & course build

- the employer’s side of the story

- efficiency in adult learning and training

- two international stakeholder meetings (April 2021, Belgium – May 2022, Austria)

- one international conference (May 2023 – Slovakia)

- communication strategy template

- an impact measurement tool

- translation of all gathered material in the inspiration toolbox

- course: jobcrafting, an introduction

- an inspiration toolbox (in the form of a website with content in different languages + links to the developed online courses in the Future Learn Platform)

EXPECTED OUTCOMES

IMMEDIATE OUTCOMES

- Enhanced access to training and qualifications for all, with a particular attention to older employees.

- New training content.

- Increased sense of initiative and entrepreneurship.

- Increased level of digital competence.

- Greater understanding and responsiveness to social, ethnic, linguistic and cultural diversity.

- Improved levels of skills for employability and job crafting.

- Increased opportunities for professional development.

- Increased motivation and satisfaction in daily work.

- Improved provision of basic and transversal skills, particularly: entrepreneurship, social, civic, intercultural and language competences, critical thinking, digital skills and media literacy

INTERMEDIATE OUTCOMES

- Methodologies for unlocking 21st century skills at work.

- Improve and extended supply of high quality learning opportunities for adults at the work place.

- Increased access to upskilling pathways for adults allowing for enhancing literacy, numeracy and digital competences, as well as other key competences.

- More positive attitude towards the European project and the EU values.

- Better understanding and recognition of skills and qualifications in Europe and beyond.

- Better understanding of interconnections between formal, non-formal education, vocational training, other forms of learning and the labour market.

CONTEXT

“We all have to work longer, we are living longer, getting older and will have to work longer.”

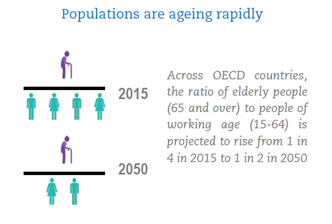

Society is ageing rapidly: across OECD countries the ratio of elderly people (65 and over) to people of working age (15-64) is projected to rise from 1 in 4 in 2015 to 1 in 2 in 2050. Governments and stakeholders urge for measures to keep people professionally active for as long as possible. The statutory retirement age is rising. But the employment rate for workers aged 55-64 is low. The accessibility rate of learning opportunities for older employees is of the lowest. Adding to this, with age comes physical vulnerability, which can play a role in various jobs. The workplace and job content should at least not amount to aggravation. Workability is decreasing instead of increasing, which is alarming when considering that we are actually expected to continue our working careers longer while mental fatigue amongst employees is rising, well-being at work is declining, learning opportunities are not equally accessible and work-life balance is hard to manage.

The challenges and opportunities for employees aged 55 and up, are embedded in a global society that is dealing with an increasing degree of digitization. A substantial percentage of European citizens are at risk of being digitally excluded. In the digitizing society, this means that they are also socially excluded, thereby compromising access to social rights.

The 21st century skills are an adequate frame for addressing durable employability of employees aged 55 and up.

OESO (2018) Policy Brief on Ageing and Employment. Aanbeveling van de Raad over vergrijzing en emlpoyment, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/public/doc/333/333.en.pdf (19 maart 2020).

“Growing in age and growing in vulnerabilities.”

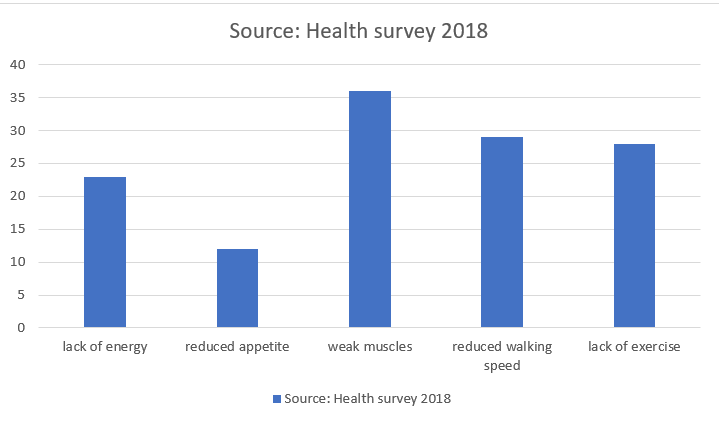

The older we get, the more vulnerable we become. The Belgian Institute of Health (Sciensano) uses 5 dimensions in its 2018 health survey to measure the physical reserves of the elderly. The graph below shows the results for Flanders (from left to right: lack of energy, reduced appetite, weak muscles, reduced walking speed, lack of exercise). As age progresses, the number of problems increases in all dimensions.

We observe a significant vulnerability to the 5 dimensions during the ages of 65 to 74, with vulnerability manifesting. As we move towards working longer (the retirement age is set to 67 years by 2030), employers, employees, and policymakers must take these indications into account. Serious health problems (such as chronic illnesses) can be prevented in a timely manner through prevention and early detection. The workplace and/or job content should not exacerbate these issues. Job crafting and a meaningful transition to another job or role can be means of prevention and provide space for rehabilitation while the employee stays on board.

“workability”

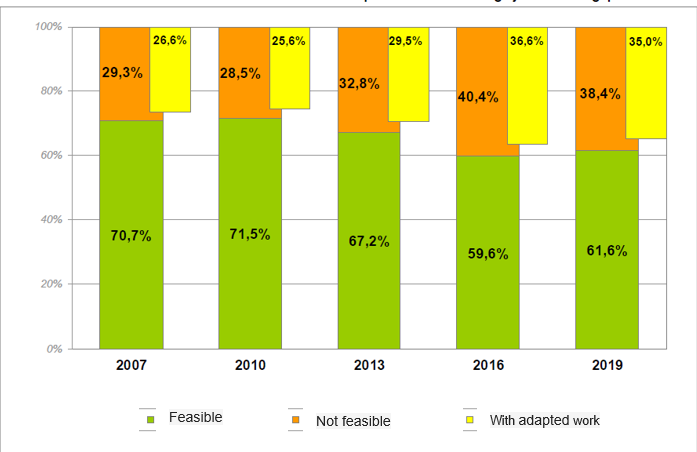

The workability rate in 2019 was 49.6%, marking a significant decrease compared to 2016 (51.0%) and 2013 (54.6%). This reverses the positive trend in workability that was observed in the previous decade. In comparison to the baseline measurement in 2004 (workability rate of 52.3%), there has been a significant decline of 2.7 percentage points. This falls short of the ambitious growth path set out in the Pact 2020, which aimed for an annual increase in workability rate of 0.5%. The goal of achieving a workability level of at least 60% by 2020 will not be met. The workability targets set out in the Vilvoorde Pact and the Pact 2020 were motivated by concerns from Flemish social partners and policymakers to increase employment, particularly for older workers, and the belief that job quality is a key factor in sustainable employability. The workability survey, which has been conducted since 2007, assesses the feasibility of longer working lives by asking: “Do you think you can continue in your current job until you retire?” Respondents who answer negatively are asked an additional question: “Would adapted work (lighter work, part-time work, etc.) allow you to work until your retirement?” The response scores for the different measurements only relate to employees aged 40 or older, who are more likely to reflect on their own career end and retirement issues. The figure below shows the trend from 2007 to 2019 of the estimates made by workers over the age of 40 in the Flemish labor market regarding the feasibility of working until retirement age in their current job or with adapted work.

Vlaamse werkbaarheidsmonitor werknemers – meting 2019. (z.d.). SERV. https://www.serv.be/stichting/project/vlaamse-werkbaarheidsmonitor-werknemers-meting-2019

The green and orange sub-bars refer to the percentage within the research population above the age of 40 who indicate that it is feasible to continue working in their current job until retirement versus those who say it is not feasible. The shifted yellow blocks in each bar represent the portion of respondents (centered on the total research population over 40) who estimate that it is not possible to continue working in their current job until retirement, but it would be feasible if their work were adapted.

The Workability Monitor not only assesses the extent to which jobs are workable for the employees involved but also identifies a number of underlying determinants and/or risk factors in the work situation. Six risk indicators have been developed for this purpose: workload, emotional stress, task variation, autonomy, support from direct management, and stressful physical working conditions.

As we work longer, the degree of workability decreases. To keep us on board, measures must be taken that have an impact on mental fatigue, well-being at work, learning opportunities, and work-life balance (the indicators used by the Workability Monitor). At the same time, attention must be paid to the risk indicators (workload, emotional stress, task variation, autonomy, support from direct management, and stressful physical working conditions).

“One way to address these indicators is through training and improving 21st century skills such as digital skills, innovation and adaptation and workplace culture.”

Digital competence has become crucial for employability. Not only because of its role as a transversal skill to develop employability, but also because about 85% of all jobs in the EU require at least a basic level of digital skills. The stakeholder consultation workshop in Bilbao in 2019 showed that 43% of the EU population had insufficient digital skills in 2017 (no skills or a low level). Additionally, 10% of the EU workforce in the same year had no digital skills, mainly because they did not use the internet, and 35% did not have at least basic digital skills, which are now required in most jobs.

Recent research has shown that as technology automates certain tasks, the value of skills required for non-automatable tasks, such as social skills, also increases. As a result, workers will need to be able to take on complex, less automated tasks, such as problem-solving in new situations while working with new technologies. This requires strong skills in reading, writing, math, and problem-solving, as well as autonomy, coordination, and collaboration skills that complement ICT skills.

According to a 2011 survey, the top five skills that employers identified as very important or important were: Interpersonal skills (100%); Time management (100%); Speaking/oral communication (98%); Ethical understanding (98%); and Adapting to change/flexibility (96%).

Skills are interconnected, and selecting only one or just one cluster is artificial in most cases. For example, during the 2019 stakeholder table on the Digital Competence Framework, participants indicated that “some of the barriers to acquiring digital competence are related to individual psychological approaches to technology, including resistance, fear, etc. For some target groups, digital training actions must include specific approaches to address these barriers related to individual mindset.”

The report, College Learning for the New Global Century (Association of American Colleges and Universities, 2008) provides insight into the answers to the question “What knowledge, skills, and competencies are identified by employers as important for success in the workplace” – a study commissioned by the Association of American Colleges and Universities in 2008. Among the skills identified by employers as highly important were: concepts and new developments in science and technology (82%); teamwork skills and the ability to work with others in diverse group environments (76%); critical thinking and analytical reasoning (73%); global issues and developments and their implications for the future (72%); the ability to locate, organize, and evaluate information from multiple sources; innovative and creative thinking (70%); the ability to solve complex problems (64%).

“Post-COVID: What Comes Next?”

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on 21st-century skills, particularly digital skills. Studies conducted by the Antwerp Management School, HRPro.be, and VBO demonstrate, one year after the onset of the pandemic, the extent to which COVID-19 has affected human capital within organizations.

28% OF EMPLOYEES DID NOT FEEL CONNECTED TO THEIR ORGANIZATION.

For numerous companies, the pandemic unfolded into a crisis of connectedness. The significance that work carries extends beyond mere salary or tasks; it also encompasses the connection with others. In April 2021, one year after the onset of the coronavirus crisis, 28% of surveyed employees indicate that they do not experience a sense of connection with the organization, while 23% lack this feeling towards their colleagues.

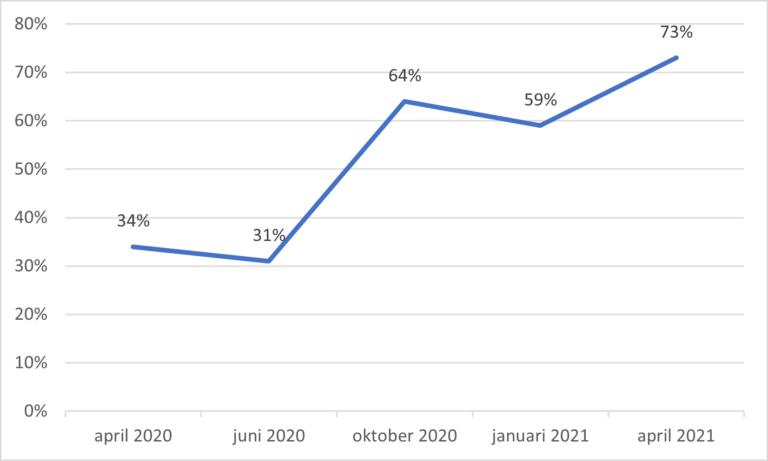

Employers are also recognizing this. As the pandemic progresses, they observe an increasing struggle in meeting the need for connectedness among their employees (see figure).

Figure: Percentage of employers indicating difficulty in fostering employee engagement

https://www.vbo.be/actiedomeinen/hr–personeel/hr–personeel/1-jaar-onderzoek-rond-de-impact-van-corona-op-menselijk-kapitaal-in-organisaties_2021-06-22/

“The Digital Knowledge Gap in the Labor Market”

The ongoing COVID-19 crisis has accelerated the digitization of our society. Innovations such as artificial intelligence and machine learning are compelling businesses to take action. After all, the ability to analyze and interpret data is becoming increasingly important. Employees across various sectors must become familiar with future-proof, digital skills. In the “Skills of Tomorrow Report 2021” by digital educator Growth Tribe, over 1,500 marketing and data professionals, along with 25 managers from leading European companies, discuss the (digital) changes in the work environment. The research reveals that more than 44 percent of professionals lack or inadequately possess these skills, putting them at risk of losing their connection to the job market.

The COVID-19 crisis underscores the significance of continuous employee development. Lifelong Learning contributes to the job satisfaction, career success, and sustainable employability of many workers. Research from the CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis indicates a positive correlation between employees with strong digital skills and positive labor market outcomes. Employees with better digital skills generally have higher-paying jobs and higher hourly wages.

Mo Gawdat, former Chief Business Officer at Google X, asserts that happy employees collaborate better, are more productive, creative, and innovative. Equipped with the right digital skills, employees are better prepared for societal shifts, contributing to their job satisfaction.

https://www.circle8.nl/talent-topics/de-digitale-kenniskloof-op-de-arbeidsmarkt